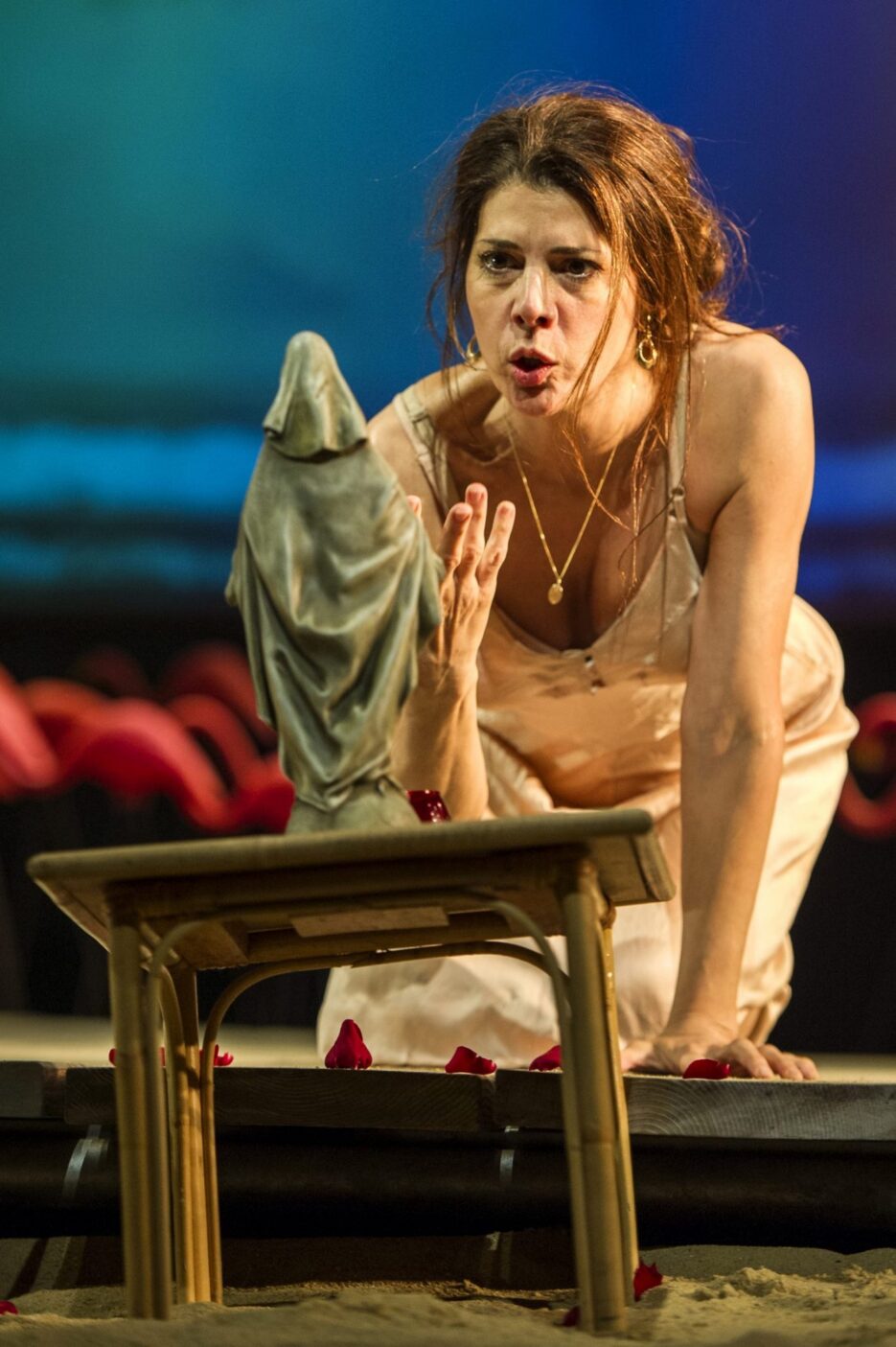

By Tennessee Williams Directed by Trip Cullman With Christopher Abbott, Sarah Chalfie, Leslie Fray, Katie Lee Hill, Lindsay Mendez, Darren Pettie, Portia, Will Pullen, Barbara Rosenblat, Medina Senghore, Hannah Shealy, Constance Shulman, Marisa Tomei, Nicole Villamil

Obie Award-winner Trip Cullman directs Academy Award-winner Marisa Tomei in this new production of Pulitzer Prize-winner Tennessee Williams’ intoxicating comedy, which won the Tony Award for Best Play in 1951. After retreating in grief, widow Serafina (Tomei) revives and rejoins the world when the hot-blooded trucker Alvaro (Christopher Abbott) arrives at her doorstep. Passion, gossip, music and mystery fill the air in this steamy Gulf Coast town, where possibility and promise ignite.

The Rose Tattoo runs 2 hours and 15 minutes, with one 15-minute intermission.

BEYOND THE FESTIVAL

The Rose Tattoo will open on Broadway at Roundabout Theatre Company on October 15, 2019.